Being different is a good thing.

It means you’re brave enough to be yourself.

– Karen Salmansohn

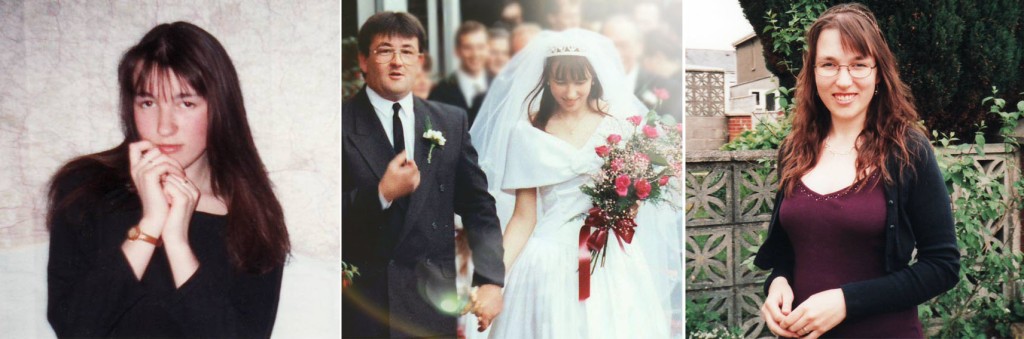

When I was young I was painfully shy and shut myself away from people, lost in a world of reading, writing, and drawing. In nursery school I would head for the paint pots or book corner, or ride a tricycle around the playground. At home I’d swing as high as I could on our garden swing, listening to music on my personal stereo, as I disappeared into my own world in the clouds. I excelled in art and writing at school, but struggled with social situations. When things got too much, when I got overwhelmed or panicked, I ran away. I was trusting and naive which lead to a lot of being taken advantage of in various situations. I found I was able to fit in more as I got older, once I learned to be who people wanted me to be.

I learned to mask. Masking is a term used to describe how autistic people try to fit into a neurotypical society, by copying or mimicking behaviour to assimilate, supressing behaviour that might be considered odd, and developing methods to cope like creating scripts for situations, routines, and more. We change our natural responses to fit in.

I’d never heard of autism when I was young. I had a long standing eating disorder controlling food intake and weight, self-harmed, had panic attacks, ran away from school, office, home multiple times, couldn’t say no, suffered crippling feelings of guilt and not being enough, and had major sensory sensitivities. I was misdiagnosed time and time again from the age of 18 upwards. I was diagnosed with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS or Post Viral Fatigue or ME – Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) at 19 when I began collapsing with exhaustion. Then I was diagnosed with chronic depression and put on a multitude of antidepressants that really didn’t work well over the next thirty years, and left to it.

I married young and had three children. As Rayn, my oldest, grew up, they struggled a lot with fitting in, with behaviour, and school was a nightmare. In Junior school I got used to phone calls asking me to come and take Rayn home, to extricate them from the toilets where they’d hidden, to catch them on the school field where a teacher hadn’t been able to, to collect them after violent behaviour. As they moved into their teens we tried to get help. There wasn’t much available, and at first we looked into bipolar as a possible reason. My younger sister had been diagnosed with hyperactivity disorder as a child, and bipolar as an adult, and later autism. In the end, Rayn was dismissed by CAMHS – Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, as just a fifteen-year-old hormonal teen.

Autism was looked at as a predominantly male condition, and girls and women were (and still are) often overlooked. Telling my child, to their face, that they were just a hormonal teen and needed to grow up was literally the worst thing they could have said. Rayn closed down, and it took another six years before they could begin to ask for help again. Rayn researched autism and after a few years finally got an assessment.

At the video assessment (during Covid) the assessor finished and immediately told Rayn that they were autistic. Usually you’d wait for the official diagnosis letter to come through before you knew, but the assessor said it was so obvious, and they were so sad that Rayn had been so badly let down before. Rayn and I cried with relief and validation. I wish we’d known when they were at school. As an adult there is no active support when you are diagnosed, but I believe as a child there are many accommodations you can ask for and get support at school. We can still ask for considerations and accommodations at work and for medical situations, but it’s more precarious.

When Rayn had begun to research autism before assessment, we’d talked a lot and Rayn said I should get assessed too. I wasn’t sure, but the more I looked at it, the more I saw myself, so I got referred.

I still struggle with any social situation, with no idea how to make small talk, and not knowing when to speak, or to stop oversharing. I can’t deal with crowds, noise, changed plans, broken routines, and I often miss jokes or sarcasm. I hate change, I panic if my favourite toothpaste, or body lotion, or food is discontinued. I hate people visiting my house unless they’re family. I have misophonia sensitivity to noises and sounds, and misokinesia sensitivity to movement or things in my eye line. I’m also sensitive to materials, smells, and touch. I hate being hugged unless I initiate it or already know and like the person. I need meticulous order, plans, and routine. I can’t bear telephones or making phone calls. I’m obsessive, I catastrophise, and my imagination is far too big! I struggle to hear people, not because I can’t hear them, but because I have to process what people say as I hear it, and that takes time. I stim, stimming is repetitive self-stimulation regulatory behaviour, usually repetitive movements or noises in aid to calm or pacify. I related to being autistic so much.

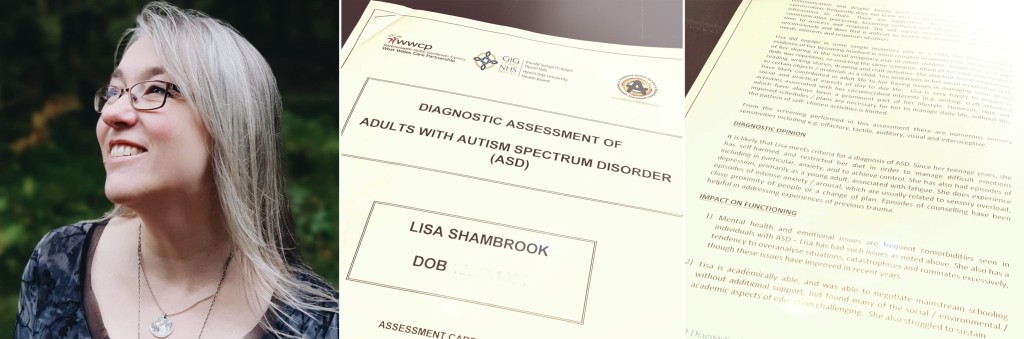

I was assessed eighteen months after Rayn, and after almost four years on the waiting list. On the second part of the assessment, my assessor wondered if my diagnosis’ of both CFS and depression was actually autistic burnout and overwhelm, that the sexual assaults I’d suffered could’ve been linked to misplaced trust, and was also the person who pointed out that my eating disorder was really ARFID Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder instead. As we talked my life suddenly made sense, and a few weeks later almost exactly on the 50th birthday I got my official autism diagnosis.

Again, so much validation, which is incredibly important, and it lead me to be able to understand myself so much more. It helped those around me to understand autism, and to see it unmasked as I began to relax and be my authentic self.

There’s a magic in being able to freely be who you are. The system is gradually catching up with autism in women, and more and more older women, who were missed when they were younger, have been receiving assessment and diagnosis.

It was recently reported that over 122,000 people are currently waiting for autism assessment in England, with long waiting lists. I don’t know the figures in Wales, but more than 2,200 children are currently waiting in my local Hywel Dda Health Authority in Wales. More needs to done and understood to improve lives.

Trying to fit into a neurotypical society is tough for a person with neurodivergent mind. Autism is not a mental health illness, our brains are just wired differently, a neurological condition. It’s estimated that 15% of the UK population are neurodivergent and 15 – 20% of world population.

And there’s a very pertinent quote from Stephen Shore, an American Autistic professor of special education, If you’ve met one person with Autism, you’ve met one person with Autism. Don’t compare one autistic person to another; every single one of us is different.

Autism is a spectrum. Think of it like a wheel with different symptoms radiating out, any autistic person could be anywhere on that circle in a number of different places. Though some autistic people will need a lot more support than others, it is not a sliding scale of most affected to least affected. It’s much more varied than that. Regardless, understanding and compassion is paramount to acceptance as a society and for us to accept ourselves. Being different is hard for anyone, but we are just as important in society as anyone else.

It’s been a revelation to accept myself for who I am, and to understand who I am. I now know I don’t need to fit in, I don’t need to belong, because, in my own way, I already do.

The potential of those of us on the autism spectrum is

unlimited – just like with everyone else – Dr Stephen Shore